Translate

Thursday, December 31, 2020

Félix Fénéon: The Anarchist and the Avant-Garde

These four installment chapters are drawn from an exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art on Félix Fénéon, 1861-1944. "One of the most influential figures in the history of modern art is also one of the least know: Félix Fénéon, a Fresh art critic, editor, publisher, dealer, collector, and anarchist who was active in Paris during the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Fénéon tirelessly advocated for avant-garde art, literature, and politics, working behind the scenes for more than five decades.

He began his career as a critic, contributing to dozens of progressive journals in the a880's and 1890's. In 1886, he coined the term New-Impressionism to describe the work of Seurat and Signac, the first of many modern artists he would ardently champion.In the early twentieth century he became a dealer and engaged with a new generation of artists, signing Henri Matisse to his first gallery contract in 1909, and giving the Italian Futurists their breakthrough exhibition in 1912. As a patron, Fénéon amasses an extraordinary collection of paintings by Seurat, Signac, Matisse, PierreBonnard, Modigliani, and may others. H was also one of the first European collectors of art from Africa, Oceania and the Americas and he endeavored to bring recognition to such works. His anarchism- for which he was arrested, in connection with bombing in 1894- shaped his belief that art could play a fundamental role in the formation of more just and harmonious world."

Fénéon and Neo-Impressionism

Félix Fénéon coined the term Neo-Impressionism in 1886 to describe a style founded by Georges Seurat and was a champion of many of the artists, especially Seurat and Signac. It was involved with political theories of anarchism and scientific studies of light and color.

Henri, Edmond Cross, French, The Golden Isles, 1891-92.

Fénéon: "I aspire only to silence."

"The most sensational of the myriad exhibitions that Fénéon organized was 'The Italian Futurist Painters' in February 1912. Launched three years earlier, Futurist paintings combined the color principles of the New-Impressionists and the fractured forms of the rivaling Cubists with their own distinctive subject matter: revolutionary politics and the speed and dynamism of the modern experience. While the exhibition received mostly negative reviews, partly in response to the artists' bombastic rhetoric, it drew huge crowds and catapulted the Futurists into the European avant-garde."

Luigi Russell, Italian, The Revolt. c. 1911.

Giacomo Balla, Italian, Street Light, c. 1910-11.

Fénéon also was one of the first Europeans to champion art from Africa, Oceania and the Americas.

Fénéon worked in a prestigious gallery and collected art himself, promoting artists that were not well known and struggling at the time, but who became famous and successful later (Matisse).

''I aspire only to silence, ' Fénéon once said. He realized this aim toward the end of his life in the ultimate act of self-erasure; rather than bequeathing his art collection to a French museum, he decided to disperse it through a series of auctions. The first took place in December 1941, when he needed funds for cancer-related bills. Following his death in 1944, and that of his wife Fanny in 1946, more than eight hundred remaining works were sold in four record-setting sales: three for his collection of art from Europe, and one for his collection of objects and sculptures from Africa, Oceania and the Americas."

Anarchy and Neo-Impressionism: Signac

"Anarchism flourished during the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries in France, a period often referred to as the Belle Époque. Though celebrated for its extraordinary cultural achievements, the era saw horrendous economic devastation for the working class, instilling in many a profound distrust of state institutions. Anarchists like Fénéon and his artist friend Paul Signac believed that the dissolution of the government, capitalism, and the bourgeoisie would allow social harmony, economic fairness, and artistic freedom to prevail."

Paul Signac, French, Sunday. c. 1888-90. "Signac subtly criticizes bourgeois ideals by painting a bored couple in their ornate Parisian living room on a gloomy Sunday afternoon. Despite their middle-class comfort, husband and wife are turned away from each other, alone with their separate thoughts. Signac's use of taut geometries reinforces the rigidity of the mood."

Abstraction: The Red Square

This and the following four installment chapters are from another exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art: Engineer, Agitator, Constructor: The Artist Reinvented.

The examples of posters, photomontages, magazines, and paintings illustrate the fertilization and tension between art and politics, advertising and uses of art to manipulate people's behavior. The show is particularly rich with art from the Soviet Union after the Revolution and into the 1930's, 'agitation propaganda.'

Following are selections on abstraction, a leading Latvian graphic artist Gustav Klutsis, a selection of Soviet women artists, a few German examples, and finally art and advertising. Quotation marks indicate text taken from museum labels.

"Abstraction for Radical Ends: Already committed to Kazimir Malevich's Suprematism, an approach he first presented in 1915 that rejected the deliberate illusions of representational painting, many artists in Russia responded to the imperatives of the 1917 Russian Revolution by deploying abstraction for radical ends. Basic shapers were utilizes, as Gustav Klutsis put it, to construct 'a new reality not yet in existence,' to call, in effect, for world revolution. In the early years of Soviet Russia, the red square exemplified this utopian stance... In the following years, the red square would proliferate across Europe. While at times less explicitly agitational, it continued to represent the revolutionary impulses of this period in Russia and to embody aspirations for the new - an ongoing reminder of abstraction's experimental leap."

El Lissitzky, Russian. About Two Squares: A Suprematist Tale of Two Squares in Six Constructions. 1922.

Gustav Klutsis

"In 1919, Gustav Klutsis (1895-1938) joined both the Communist party and UNOVIS (Affirmers of the New Art), a collective of artists who sought to use abstraction for agitational purposes. Klutsis's photomontage embodies these dual commitments. While some of the photographic elements have deteriorated or been lost, the combination of approaches - simplified geometries exemplified by the red square and cut and pasted photographs calling out the ambitions of the new Soviet order - suggests the work may have been created in two stages: begun in the spirit of UNOVIS and reworked after Vladimir Lenin's death in January 1924. The printed text refers to Lenin's famous slogan of 1920, 'Communism = Soviet power plus the electrification of the entire country.'"

Gustave Klutsis, Latvian, "Electrification of the Entire Country", c. 1920.

Gustav Klutsis, Maquette for 'Plan for Socialist Offensive' magazine spread, for 30 Days. 1929.

Gustav Klutsis, Latvian. 'Maquette for the poster 'The Reality of Our Program is Real People - That is You and Me'. 1931. 'Photomontage is an agitation-propaganda form of art,' Gustav Klutsis declared. This poster depicts Joseph Stalin as a man of the people, striding alongside workers representing a variety of occupations. The title is from a 1931 speech in which he promoted higher wages for technical specialists as a way to improve industrial productivity; the imagery reiterates the slogan's anti-elitism. Preparatory designs reveal how Klutsis experimented to create a poster with maximum visual power, cutting and rephotographing his source material and pasting elements in different configurations to determine his finished composition. In 1931, the year this work was published, Stalin's regime centralized power production, which enabled the state to censor artists and control their output, including dictating that the leader personify socialism. Artists once drawn to the utopianism of the revolution found themselves enlisted to mobilize the masses in support of a dictatorship. Despite his years of service, Klutsis was executed in 1938 for being 'an enemy of the state.'"

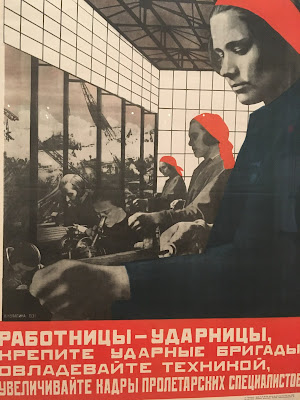

Soviet Propaganda Women Artists

"WOMEN AS PRODUCERS AND CONSUMERS: Joseph Stalin's first Five-Year Plan (1928-1932), which aimed to increase industrial productivity and the construction of public infrastructure, created an urgency for Soviet women to enter the workforce. A campaign for a 'new everyday life' (novyi byt), in which the state would provide services such as childcare, cafeterias, and public laundries, sought to free women from domestic duties and enable them to work outside the home, in factories and communal farms, for example. Central to this initiative was the creation of posters, often by women artists assigned to the theme, representing new ways female citizens could be producers and consumers in Soviet society. These artists sought to reach a wide public as they shaped the socialist ideal of gender equality."

Valentina Kulagina, Russian, Maquette for We are Building - Stroim. 1929. "In 1929, no skyscrapers had yet been built in the Soviet Union. Nevertheless, Kulagina created an aspirational vision of Soviet architecture. With 'We are building' spanning the cityscape, this maquette promoted Stalin's First Five-Year Plan (1928-32), which supported public infrastructure projects as part of a program to increase the nation's industrial productivity. Kulagina combined printed images of American architecture, such as the Detroit skyscraper at right, with hand-drawn elements, and inserted sandpaper to suggest the texture of concrete."

Liubov Popova, Russian. "Long Live the Dictatorship of the Proletariat!". 1923. Set design for the play 'Earth in Turmoil.'

Natalia Pinus, Russian, "Women Workers, Women Collective Farmers, Be in the Front Lines of Fighters for the Second Five-Year Plan for Building a Classless, Socialist Society!" 1933.

German Posters from the Twenties

The poster below is a famous image demonstrating the intention of modern designers in Germany in the late 1920's to leave behind stuffy turn of the century interior and home design and move toward modern design of the future. The poster was done by Willi Baumeister in 1927 for an exhibition organized at the Weissenhofsiedlung in Stuttgart, Germany. The typography asks 'How to live (at home)?'

Campaign poster for the German Communist Party. John Heartfield/Helmut Herzfeld. The Hand Has Five Fingers. 1928.

Poster for municipal pools, Augsburg Germany, 1928. Werner David Feist.

"Soon after designing this poster, Feist was banned from those same pools because he was Jewish." Ironically, the photo is of Feist himself.

Max Burchartz, German, Untitled (red square), c. 1928.

The Artist as Adman

"The word MERZ is nothing more than the second syllable of Commerz," Kurt Schwitters explained of his branding of his one-man art movement.... As a fine artist, Schwitters gathered urban detritus into collages. In 1924, he established the advertising agency Merz Werbezentral to address a broader public, shape its appreciation for functional design, and harness a stable income. Based in Hannover Germany, the agency, later renamed Werbe--Gestaltung, served a range of clients, from a furniture maker to the city's streetcar company. Combining bold, often asymmetrical layouts, typographic elements reflecting information hierarchies, and photography, his designs emphasized split-second legibility for busy viewers."

Poster for Dammerstock Housing Development. Karlsruhe Germany. 1929. Kurt Schwitters.

"Advertising-Constructors: We understand perfectly well the power of agitation... The bourgeoisie understands the power of advertising. Advertising is industrial, commercial agitation," wrote the Russian poet Vladimir Mayakovsky in the period of the Soviet Union's New Economic Policy (1921-1928), when capitalist-style commerce was temporarily endorsed. Determining that new conditions in the years following the Russian Revolution demanded a new civically engaged role for artists and poets, Mayakovsky and the artist Aleksandr Rodchenko formed the advertising agency Reklam-Konstruktor (Advertising-Constructor). Rodchenko designed the bold graphics while Mayakovsky contributed the pithy slogans.... As advertisers, their goal was not simply to sell such products as light bulbs and cigarettes, but to compel consumers to support the new state: to spark their desire for socialist objects and to transform that consumerist longing into a civic one, to shop as responsible Soviet citizens."

The poster below is advertising Tea Directorate Cocoa Powder. The word slogans are:

COMRADES, THERE'S NO DEBATE, SOVIET CITIZENS, WILL GET IN GREAT SHAPE, WHAT IS OURS, IS IN OUR POWER, WHERE'S OUR POWER?, IN THIS COCOA POWDER

Max Bill, Swiss, Poster for exhibition on the Neubühl housing project, Zurich, 1931.